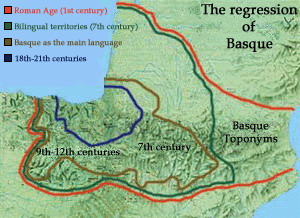

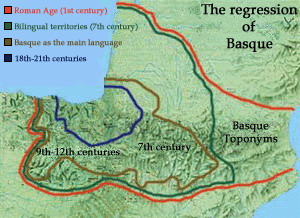

At the present time, Linguistics does not consider as proven the existence of the Basque linguistic substratum beyond the Basque Country, the Pyrenean area and the southern half of France. However, there have been some linguists that held the idea that this substratum also extended throughout the whole northern third of the Iberian peninsula. One of them was the linguist Antonio Tovar (Valladolid, Spain), who in the last century spoke about the existence of a possible Basque substratum that reached the region of Galicia. This theory is supported by the phonetic and lexical similarities that are common to the currently spoken languages that are comprised in the northern third of the peninsula and southern half of France. According to this hypothesis, the origin of those similarities would be in the Basque language.

Regarding the common lexical aspect, it must be pointed out that Portuguese (esquerda), Galician (esquerda), Astur-Leonese (izquierda), Castilian (izquierda), Catalonian (esquerra) and Occitan (esquèrra), with the exception of Gascon (gaucha) and Aragonese (cucha, which comes from the Gascon term), use the same word of Basque origin instead of the Latin term that was expected: sinistra (left).

Regarding the common lexical aspect, it must be pointed out that Portuguese (esquerda), Galician (esquerda), Astur-Leonese (izquierda), Castilian (izquierda), Catalonian (esquerra) and Occitan (esquèrra), with the exception of Gascon (gaucha) and Aragonese (cucha, which comes from the Gascon term), use the same word of Basque origin instead of the Latin term that was expected: sinistra (left).

The term 'left' is said ezkerra in the Basque language that comes in turn from the words 'esku' (hand) and 'oker' (twisted). On the other hand, the Basque terms eskuma, eskuin and eskubi, which all mean 'right', come as well from the words 'esku' (hand) and 'on' (good).

Another example that is similar to 'ezkerra' is the archaic term ibaika (from the Basque word 'ibai', that means 'river'), which gave rise to the Spanish word 'vega' and the Galician word 'veiga' (meadow). There is another Basque widely-used term: naba (in Spanish nava: plain land among the mountains).

Another example that is similar to 'ezkerra' is the archaic term ibaika (from the Basque word 'ibai', that means 'river'), which gave rise to the Spanish word 'vega' and the Galician word 'veiga' (meadow). There is another Basque widely-used term: naba (in Spanish nava: plain land among the mountains).

According to this theory, the Basque substratum existed in the whole northern third of the peninsula and southern half of France before the arrival of the Indo-Europeans. Some linguists, historians, archaeologists and anthropologists go even further when they say that the Basque language as well as the Basque people descend from the Magdalenian hunters and gatherers that gave rise to the Franco-Cantabrian civilization. (It reached its peak from 15000 B.C. to 9500 B.C. and created the beautiful cave paintings of Altamira in Cantabria, Santimamiñe in Biscay, Ekain in Guipúzcoa or Isturitz in Lower Navarre).

The linguists that support this theory affirm that the areas, in which most remains of this prehistoric culture have been found, exactly match the extension of the lexical and phonetic similarities that show the different peninsular languages and the ones from the southern half of France concerning the Basque language. Therefore, the Franco-Cantabrian civilization was none other than the Proto-Basque culture and the current Basque culture would be its heir.

Other Basque linguistic features or rather phonetic features that match the geographical extension of the Franco-Cantabrian civilization, according to this theory, is the opposition between /r/ and /rr/ when they are placed between two vowels, as well as the lost of the Basque intervocalic /n/ in Galician: bona (Latin) > boa (Galician); buena (Castilian) and in Gascon: laguna (Latin) > lagua (Gascon), laguna (Castilian). Finally, the lack of the voiced labiodental fricative phoneme /v/ in the Galician, Astur-Leonese, Castilian, Aragonese, Catalonian and Gascon phonological systems (although it is present in Portuguese, old southern Castilian and Valencian).

The reason of that /rr/ is pronounced in Portuguese (which is an evolution of the Galician language) like the French /r/, instead of being pronounced like the Galician or Basque /rr/, or that the sound of /v/ is not pronounced like /b/ in the Valencian dialect of Catalonian and in old southern Castilian is due to the lack of Basque substratum in Portugal, Valencia and the southern area of Castile, according to this theory. This fact prevented Portugueses, Valencians and southern Castilians from pronouncing like Galicians, Catalonians and northern Castilians respectively.

On the other hand, the evolution of the sound /f/ into aspirated /h/, which is tipical in the Basque phonetics, is not only found in initial Castilian [fabulare (Latin) > hablar (to speak)] or in Gascon [facere (Latin) > har (Gascon); to do], but also in the areas of the Astur-Leonese linguistic scope: [fabulare (Latin) > jalar (eastern Astur-Leonese)] instead of 'falar' (to speak), which is the appropriate form in Astur-Leonese. According to the theory, those linguistic details denote an ancient extension of Proto-Basque at least up to part of Asturias and the northwest area of Castile and León.

Share this page!

Another example that is similar to 'ezkerra' is the archaic term ibaika (from the Basque word 'ibai', that means 'river'), which gave rise to the Spanish word 'vega' and the Galician word 'veiga' (meadow). There is another Basque widely-used term: naba (in Spanish nava: plain land among the mountains).

Another example that is similar to 'ezkerra' is the archaic term ibaika (from the Basque word 'ibai', that means 'river'), which gave rise to the Spanish word 'vega' and the Galician word 'veiga' (meadow). There is another Basque widely-used term: naba (in Spanish nava: plain land among the mountains).